![platoaristotle]()

*Disclaimer: This is an opinion piece that reflects solely my own personal views.

Imagine that you are on a ship. You have been on this ship for years. Maybe you were even born on this ship. Every day, you wake up and make your contribution to the running of the ship. You help clean the decks, check it for damage, contribute to its upkeep, pay your dues like everyone else on the ship so that new nuts and bolts can be purchased and the ship keeps sailing.

Because it matters to you that the ship sails steadily and is seaworthy. You live on it, after all! If it sinks, you go down with it. When it sails in calm seas, you along with everyone else take a deep breath and enjoy the ride. When it hits a bad storm, you along with everyone else gather the sails and ride out your own seasickness with your fellow shipmates.

But there is something you’re very aware of – you belong to a minority that contributes just like everyone else, but you are not allowed to help choose who the next captain of the ship will be. From time to time, you pass other different ships in the sea. Some of them have old crew members from your own ship who left a few years ago, and they tell you that there’s talk of them being allowed to help choose the next new captain. They don’t live or work on this ship any more while you still do, but you are not allowed this same right.

Maybe one day when you’re on shore, you’re lamenting this situation at a seaside tavern, drinking ale with other members of your ship when a few of the turn to you and angrily tell you “You have no right to pick the captain. Go back to your old ship if you don’t like it.”

And you stare into your stein and sigh, because you get told this so often. Then you look back at the sea where your beloved ship is docked, and you wish that along with taking care of it and helping it run, the powers that be would let you at least help pick the captain, like the other crew members. Somewhere far out to sea are two old ships you once used to sail on, but they are not your home any more.

This ship bobbing on the waves just off the coast is. And you get tired of being told again and again that you are not as much of a contributing crew member to your ship, just because you have a different set of papers. So you finish your ale and slip out of the tavern to take a walk while the other crew members make plans for who they think they’ll pick for their next captain. Joining in seems futile, because it doesn’t matter how well you know the policies of the captain or whether your ship will stay afloat with their ideas. You don’t get to choose, because as those angry crew members told you, you are not of this ship.

****

In a few days, Greeks head to the polls for a general election, which once more were called earlier than they were due. The last time Greece went to the polls on schedule was in 2004, when Kostas Karamanlis’s government won on the New Democracy ticket, and even those elections were slightly ahead of time due to the Olympic Games.

Since then, parliamentary elections were called early in 2007, then 2009 when they were due to 2011 and called again in May 2012 ahead of schedule for 2013. That same year, elections were held once more in June when no government was successfully formed after the first round.

Fast forward to 2015, when again the country endured two general elections as well as a referendum, all held ahead of schedule.

And this takes us to July 7, 2019, when elections that were due in the third quarter of the year are being held earlier than they were scheduled, meaning that in 12 years, there has not been one instance of a Greek general election that was held on schedule. Twelve years of political and economic turmoil is a long time, and I have lived the fallout – the uncertainty, the rising costs, the friends losing jobs, me and my husband losing jobs, services cut, bone-headed bureaucracy, crumbling nurseries and schools, and more.

With no way to express my voice in a democratic way, since I cannot vote as a non-Greek citizen, social media has been a way for me to track developments and comment on the line taken of various political parties, notably New Democracy and their leader, Kyriakos Mitsotakis. No matter how deeply the crisis has been felt by me, it’s quite a common phenomenon for me to be slammed for expressing a political view, especially if it’s a strongly worded one.

A few months ago, I posted some tweets seemed to anger a lot of people, which appear below.

I expressed an opinion, which is my right to do, but if there is one thing I would say I did wrong, it would be that I tweeted when I was angry, which is rarely a good strategy. Truth be told, once I’d calmed down I considered deleting the tweets, but they were out there so it seemed like self-censorship to remove them once I’d said what I said.

My views were dismissed as invalid and biased, because as I was repeatedly reminded, I’m not Greek. It set off something of a troll attack that prompted me to take a clean break from Twitter for a month. The quality of my work and my ethics as a journalist were rubbished on a public forum.

If I didn’t like it, I was told, I could go back to Pakistan. Why should I get to vote in Greece when foreigners don’t get to vote in Pakistan. To this I’d say if you want to make a comparison, surely that should be in an upward direction, rather than saying a poor, largely uneducated third-world country doesn’t do XYZ, so why should we, a relatively rich and educated first world country do it? Why should we be the better of the two?

It’s even more baffling when you consider that I’m having a country pushed in my face which I haven’t lived in in 23 years and whose politics I don’t follow. I have journalistic colleagues who have lived outside of Greece for longer than I lived in Pakistan, who I am pretty sure never get told to go back to the UK, Germany or elsewhere. This appears to be the magical Twitter-Troll Shield that a Greek name can offer.

In either case, the message from these attacks when I delve into Greek politics is clear – stay in your lane. Foreigners in Greece, especially the ones who are visible ethnic minorities, are ignored the 99 percent of the time we are living ordinary lives, working, taking care of our families, paying our bills and paying our taxes. When a minority steps out of line and does something truly awful, the rest of us take the fall as a whole.

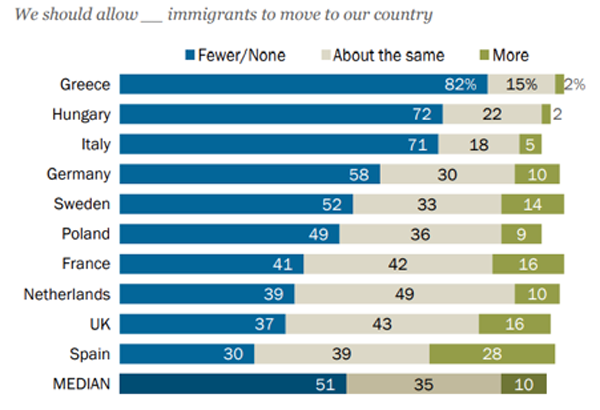

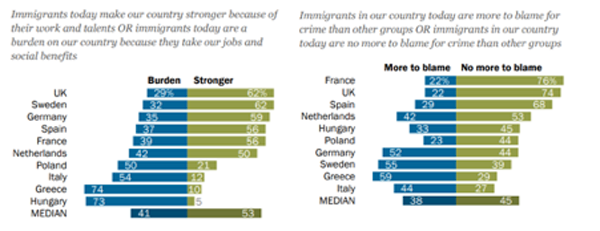

The misdemeanors of a few get recycled and constantly churned out in our directions whenever we dare to call out the government’s immigration policies – your fellow countryman was responsible for that rape/murder/violent attack, why should any more of you be let in?

An ethnic minority immigrant in Greece has to be exceptional on both ends of the scale to get noticed by the Greek media and society at large – either we must be unfathomably terrible, or unfathomably talented. The rest of us in the middle are neither, and in a strange paradox, we never get to ride on the tailcoats of the unfathomably talented (here’s looking at you, Antetokounmpo!), but we are without fail forcibly stapled to the tailcoats of the unfathomably terrible anomalies that emerge from our communities and told that this is the benchmark for who we all are.

It is hard to witness us approaching this important democratic moment and know that I can do nothing but watch. It is even harder when there are few good options to pick from. SYRIZA, having taken their chance, are almost without a doubt heading for a resounding defeat at the polls, one which many argue is deserved. And having lived through more than four years of amateur hour politics, endless uncertainty and some colourful designer shirts in parliament, we can all safely see that four years can feel like a very, very long time.

It is excruciatingly long when your child’s disability has progressed during those years and when you have to fight all the time for his inclusion in society, to demand that he and others like him get their place and their chance. And you think all the time “Why is this still like pulling teeth? How come government after government either keeps it the same or makes it harder?”

Now we come to Mitsotakis. I would very much like the next government of Greece to succeed, but I cannot ignore the divisive rhetoric Kyriakos Mitsotakis has at times taken during his campaign. My feelings stem not only from being a visible foreigner. If I stay silent when Mitsotakis and others like him use the divisive language that he has used, I feel as if I will be paving the way for a whole array of discriminatory behaviour, including against the disabled.

Let’s be clear that the markets and outside observes seem to love Mitsotakis. He is well-educated and highly experienced in a corporate and international environment. But he also seems to have no problem at all in courting the votes of the far-right. When a supposedly reformist and modern leader like Mitsotakis is aligning himself with people like Thanos Plevris, who in the past has more or less called for the deaths of immigrants at Greece’s borders, what does it say about him and his party?

This is just one example. It goes without saying that SYRIZA’s track record has also been abysmal. For a start, they aligned themselves with ANEL and ex-defence minister Panos Kammenos whose twitter feed is a stream of barely veiled or not-veiled-at-all nationalist rhetoric. This was glossed over by SYRIZA, though, so long as it allowed SYRIZA to hold on to power. Because after all, everyone can say whatever they like about immigrants, including that the SYRIZA government is dishing out Greek nationality to Pakistanis like candy in exchange for votes (not true).

They can say that Afghans and Pakistanis are receiving text messages in their own languages telling them who to vote for and how, which completely ignore the fact that you cannot show up at a polling station with a text message and expect to vote if you are not a Greek citizen who is on the electoral register.

And in the meantime, issues which I have pointed out in the past remain unchanged, including grassroots education reform and, you know, just creating a country that’s good enough for the kids who grow up here. A country that deserves the kids that grow up here.

It has taken me a good few months to put this blog post together, because whichever side I pull up, I will get criticised for it. And I have to be honest – I’m getting tired of being told to stay in my lane, to be asked what’s going on in the country I left 23 years ago, to be told on one hand that I’m biased and on the other hand to be expected to have no opinions at all.

I was at an anti-racism press conference a while back where a young Greek woman of Nigerian descent spoke, saying “We are asked to prove constantly that we are more Greek than the Greeks, more loyal than a Greek. We are held to a standard that’s much harsher than a Greek.” In this same context, a Greek who was born in Australia and only comes to Greece for the summer is much freer to express their opinion on Greek politics than a non-Greek living, working and experiencing the reality of Greece.

The over-the-top reaction I get when expressing my opinion on Greek politics is telling, since it appears that the opinion and not the issues they address spark a stronger rhetoric.

I am not interested in what the policies of Pakistan, or Zimbabwe, or Bangladesh, or Rwanda, or Guatemala or India are. I am interested in the policies of Greece, because this the ship I sail on, and this is the ship I care about. I do okay. I contribute. I add value to life here in my own small way, just like thousands of others like me. I’m not ever going to be the NBA’s most valuable player, but I do pay my taxes on time and the only crimes I have ever committed have been crimes against fashion and karaoke.

There is so much more I’d like to address, including New Democracy’s proposed 2,000 euro stipend for new born babies born in Greece as long as at least one parent is Greek (breaching EU discrimination laws) but this post is already long enough. On July 7, I will be watching and hoping for the best outcome for Greece. I hope the next leader will do a good job. I truly wish them the best and I’ll be following what they do with optimism. And perhaps one day, after I’m done swabbing the decks and checking the sails for tears, I too will get to have a say in who the next captain of this ship should be.

Have you ever been talked about in a room while you were stood there in front of the people who were doing it? I can’t say I’ve had much experience of it, apart from the early days when I was still learning Greek and people didn’t know i could understand what they were saying. Not so long ago, it happened at a gathering of Pakistani women where a couple of the other women assumed I was Greek (I can’t win) and began talking about me in Urdu.

Have you ever been talked about in a room while you were stood there in front of the people who were doing it? I can’t say I’ve had much experience of it, apart from the early days when I was still learning Greek and people didn’t know i could understand what they were saying. Not so long ago, it happened at a gathering of Pakistani women where a couple of the other women assumed I was Greek (I can’t win) and began talking about me in Urdu.

There are certain slogans that we’ve all grown used to over the years. Along with the knowledge that success requires hard work, on our hard climbs up whichever ladder it is we’ve chosen, we silently repeat to ourselves that quitters don’t quit, and failure is not an option. We’ve all seen that

There are certain slogans that we’ve all grown used to over the years. Along with the knowledge that success requires hard work, on our hard climbs up whichever ladder it is we’ve chosen, we silently repeat to ourselves that quitters don’t quit, and failure is not an option. We’ve all seen that  On the list of things that I have to do, thinking about Greek politics doesn’

On the list of things that I have to do, thinking about Greek politics doesn’

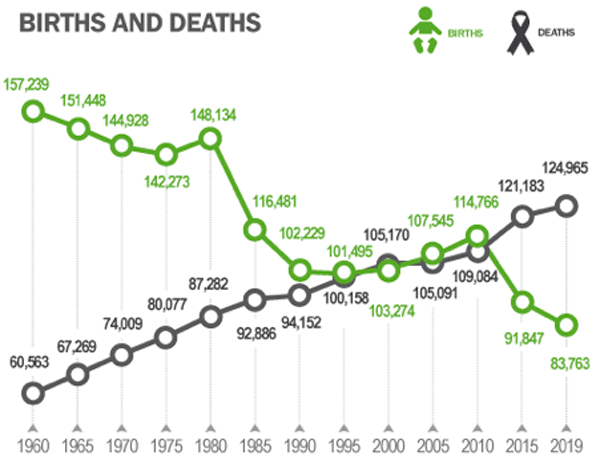

'fertility' conference. Article & conference webpage in

'fertility' conference. Article & conference webpage in  . <a href=”

. <a href=”